by Milena Gabanelli and Fabio Savelli

The first obstacle is the price: from €30K to €37K for a small road car. Too much for the average consumer, who from Federauto data can afford to spend 8 thousand euros. Additionally, there are 15 million used, diesel or gas driven cars in circulation in Italy. The government's incentive to scrap the old one and buy a hybrid or electric one is minimal: 4 thousand euros, while France and Germany have promised 14 thousand. It's like saying that we help the wealthy.

China controls the raw materials

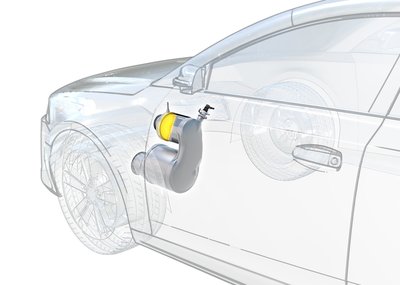

Meanwhile, manufacturers are obliged to increase the production of electricity to comply with the emission limit imposed by European standards (95 grams per km) and avoid heavy penalties. For half of the manufacturers in Europe, before the lockdown, sanctions of about 400 million euros were forecast for 2020 and 3.3 billion in 2021. The fact is that out of 80 million cars that are sold worldwide every year, only 2.1 million are electric, and half circulate in China. So to lower the price you have to sell many. The problem is that to make them go you need the battery, and you have to deal with the country that is upstream of the supply chain of raw materials necessary to produce it: cobalt, nickel, lithium.

China has almost 90% of the world's deposits under concession and also controls the know-how of the industrial process. Beijing has colonized the Congo, which is the largest producer of cobalt in the world, and torn ten-year exploitation contracts also in South America. Not having large car manufacturers, and having to reduce pollution in large megacities that have grown dramatically as a result of demographic transitions from the countryside, it immediately focused on the development of electricity. In addition, China has been investing in batteries for years for the demand for consumer electronics products - smartphones, tablets, PCs - of which it has become the world's factory. Foxconn, based in Shenzhen and with 330,000 employees, is the historical supplier of Apple, Amazon, Hp, Microsoft, Sony, BlackBerry.

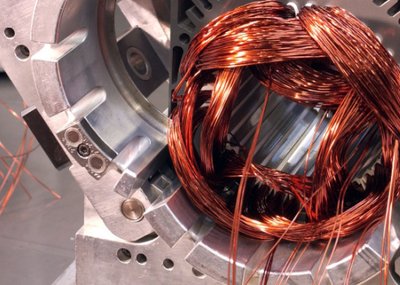

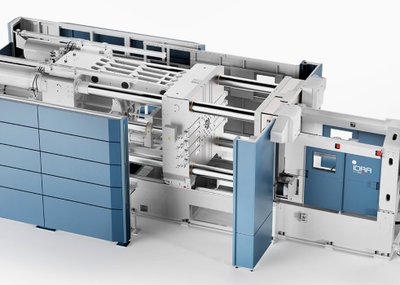

Where batteries are made

To recover the gap that binds its hands to China, European research is running and IBM is experimenting with the way to extract rare metals from seawater in the United States. But then to transform 80 million cars that are sold worldwide every year into electricity, it would take 240 gigafactories to build batteries, at a cost of two billion euros each. Today, there are three maxi-factories: that of Tesla in Nevada, the second is in China, the third in Sweden with Northvolt, just recapitalized by Volkswagen and BMW in an operation that experts have qualified as the first European move in the battle for lithium. It would already be possible to launch cars at a lower price on the market, but the demand would jump upwards, quickly depleting the stock currently available. So the big producers, while announcing maxi-investments, put expensive models on the market, precisely because by expanding the offer China would end up taking advantage of it in a geopolitical competition amplified by commercial duties.

The 60 billion investment

The EU Commission and builders are investing a lot of money: from 3 billion in 2017 to 60 billion in 2019 (China invests 17). Inside there are also loans to battery factories: across Europe there are 16 in the pipeline. None in Italy.

Yet Fiat (the last of the major manufacturers) has just launched its first electric model with the new 500 and has also had to sign an agreement with Tesla not to pay hundreds of millions of penalties. He also asked Intesa Sanpaolo for 6.3 billion euros guaranteed by the state to support the car supply chain, but among the conditions required by the Ministry of the Treasury to give the green light, there is no construction of a battery system. It could require FCA to expand its newly created electricity hub in Turin.

The effects of Covid on forecasts

According to Transport & Environment analysts, cost parity with petrol and diesel cars should occur when the platforms most used on the assembly lines of the plants will no longer be the traditional ones, but the special ones. At that point the costs will drop by 20%. It is no coincidence that FCA has chosen the French PSA (which has two supplied) for an integration that is now finished under the EU Antitrust lens. The fact remains that the Germans of Volkswagen are still driving: 75 models by 2029. The prospects for the production of electric vehicles in 2021 place Germany in first place with 870 thousand units, followed by France with 295 thousand vehicles. But these are estimates distorted by the pandemic. At the end of January, sales of electric cars across Europe were up 80%, to 6.4% in the months of March, April and May. The enormous research efforts are incompatible with the contraction in profits and the liquidity crisis of the companies triggered by the covid, which has zeroed the cash flows leaving millions of unsold (certainly not electric) cars in the car park of the dealers. A collapse in demand for 20 million cars.

The problem with the charging points

This is the first question asked by those who want to buy an electric car - and in Italy there are about 8,500 public columns installed compared to 11,000 vehicles in circulation. They are distributed in the streets, squares, parking lots, with more than half in Italy's northern regions. Few on suburban roads and highways. It takes 12 hours to fully charge, and the most comfortable place is at home. A 110% eco-bonus is foreseen to install the charging points in the common condominium areas. But 95% of the buildings do not have an electrical network capable of withstanding heavy power absorption, and in addition there are a number of bureaucratic procedures to be carried out, including communication to the Land Registry. On new buildings, through an appropriate incentive system, it is possible to push construction companies to invest in the installation, but the complexity of the operation lies entirely in the redevelopment of old condominiums, which also involves the training of administrators. Finally, there is the topic of disposal: 97 thousand tons of batteries in 2018 alone.

How batteries are recycled

The average life of a battery is 8-10 years, but after that it still has a residual capacity that can be reused for storage applications. Recycling is crucial, because it allows you to recover up to 90% of the rare materials and, therefore, not to depend completely on the Chinese monopoly. Today, Europe sends them right to China, the undisputed leader also in the field of battery recycling, for the regulatory framework it has created. Meanwhile, the first Hydro Volt joint venture to build a recycling factory has just started in Norway.

In short, we are trying to make up ground, but there is always a piece missing: cobalt, which is downstream of the process, can only be recovered at a rate of 5%. The other 95% must be found and mined. Where is it? In China. In essence, nothing can get started without going through Beijing. But in ten years, some concessions will expire and, at that point, the turning point may take place, provided that no more time is wasted. The time is right.

Source: corriere.it